Thomas Richards, Jr.

In February of 1846, as tension over the future of the vast Oregon Country heated up, former U.S. Indian Agent to Oregon Elijah White defiantly asserted the patriotism of American settlers in Oregon in a letter to the Washington Daily Union. If the United States and Great Britain went to war, White claimed that American settlers in Oregon would “defend our flag,” for they were “true to the American eagle.” Thus Britain would have difficulty conquering Oregon in a war, for Americans comprised roughly 90% of the region’s population, giving the United States a decisive on-the-ground edge in the distant territory.

But White could not have been more wrong, although whether it was from ignorance – he had not been in Oregon for several years – or from his own patriotic bluster remains uncertain. Americans in Oregon may have been “true to the American eagle,” but not to the point “defending the flag.” Indeed, that same year a letter-writer to the Oregon Spectator argued that because “the main war [between the United States and Britain] would be on the Ocean, I see no use of our fighting here…let our provisional government stand, and those who wish to stay at home and cultivate their farms, be permitted to do so without censure or molestation.” John McLoughlin, the Chief Factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), would have agreed with this statement, for he too desired peace in the region. Oregon Country, therefore, presents a curious on-the-ground anomaly during the years when Great Britain and the United States were at increasing odds and war at times appeared likely.

The explanation for this anomaly is understandable, but surprising given the tense state of U.S.-British relations at the time: by 1846 the interests of Americans of Oregon were only loosely connected to those of the United States, and the interests of the HBC officials living in Oregon were only loosely connected to the British Empire. This had not always been the case: in the early 1840s, a then much smaller population of Americans in Oregon frantically petitioned the U.S. government to extend jurisdiction over Oregon, while McLoughlin actively opposed the formation of the Oregon Provisional Government for its assertion of local sovereignty at the expense of the HBC and the British Empire. Yet prosperity and reality moderated both of these stances, demonstrating that U.S. and British nationalism may have retained powerful holds on large sections of each polity’s population, but personal economic and social interests subsumed this nationalism – at least in Oregon.

Until the mid-1830s, McLoughlin and his fellow employees of the HBC – most of whom were French Canadian – were the only Europeans who had permanently settled in Oregon. In 1824, McLoughlin had founded Fort Vancouver, situated on the current state border of Oregon and Washington, amidst thousands of indigenous Kalupuyans and Chinookans. In the following years, men employed with the HBC married Native women, forming a metis community of roughly one hundred families. This community, along with alliances McLoughlin formed with other Native peoples across the vast Oregon Country, solidified the HBC’s hold on the region, and allowed McLoughlin to assert unbridled personal authority. While HBC-Native interactions were overwhelmingly peaceful, peace could not prevent the tragic spread of European diseases, which killed perhaps 90% of the indigenous population by 1841, opening a space in a now under-populated Willamette Valley that someone could eventually fill.

In 1834, that someone was Jason Lee, a Methodist minister from the United States (technically Lee was from Quebec, but migrated to Vermont in his teens). Lee was the first of eventually dozens of Methodist and Presbyterian ministers and laypeople who came to administer to Oregon’s Native peoples. Soon a rivalry formed between these Protestant missionaries and the largely Catholic HBC community – and two Catholic priests who would join them in 1838 – but this rivalry never disrupted fundamentally peaceful relations between the HBC and the American missionaries, for neither fundamentally threatened the other’s goals.

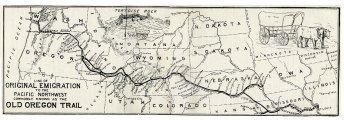

This was not the case in 1840, when a few dozen Anglo-American overlanders arrived in Oregon, having been awakened to Oregon by the writings of the missionaries and the promise of free, fertile land. This small group of migrants presaged exponentially greater numbers in the years that followed – roughly one hundred in 1841 and 1842, 875 in 1843, 1475 in 1844, and 2500 in 1845. In the first few years of American migration, the incoming settlers were overwhelmingly hostile to the HBC and its Native allies, and British power in Oregon more generally. They petitioned the federal government to annex Oregon, maintaining they were “exposed to be destroyed by the savages around them, and others that do them harm” – the “others that do them harm” referencing the HBC. These pleas were quite logical, because the first American migrants were a decided minority of the Willamette Valley’s population; they found themselves at the mercy (or at least so they imagined) of Oregon’s Natives and the British, two groups whom they were predisposed to dislike by virtue of the migrants’ Americanness. Moreover, in 1841 the HBC had facilitated the arrival of 25 families from the Red River region of British North American, and Americans in Oregon feared (and the HBC hoped) that these arrivals would be the first of many immigrants from British North America, which would counter the increasingly American population.

In all likelihood, these early American migrants were correct in their assessment that HBC and Native power could have killed them, or at least expelled them from Oregon. McLoughlin, however, had little wish to see the Americans leave, for several reasons. First, it made economic sense to allow them to remain. American migrants arrived with very few provisions, and therefore they purchased their goods from McLoughlin’s store, increasing McLoughlin’s own wealth. And, these migrants desired to farm, and would not impinge on the HBC’s fur trade. Second, it made moral sense. McLoughlin had his flaws, but he was not willing to kill or expel Americans whom he had little reason to dislike. Most came as families, and sought free land, not political dominance. After all, he and the HBC held the balance of power – or so they thought.

The 875 migrants of 1843, later known as the “Great Migration” to Oregon, fundamentally altered the region’s dynamics. In a single year, the HBC and its Native allies went from a slight majority of the population to a substantial minority, and their minority status continued to increase with each year’s American migration that followed. Now in the majority, Americans had little need to petition the United States for immediate annexation, or fear HBC and Native power. They quickly asserted their confidence, strengthening the fledgling Oregon Provisional Government by creating an executive and giving the government the ability to tax. Even more importantly, they passed a law that gave 640 acres of land to any migrant who made the journey to Oregon. This law was particularly enticing to Americans in the East who contemplated moving west. In the United States, conservative land laws that favored speculators, coupled a devastating economic depression, made it difficult to procure land, but now it was available in Oregon. No wonder thousands of Americans migrated in 1844 and 1845.

McLoughlin and the HBC families could read the writing on the wall. First, the HBC employees agreed to participate in the Oregon Provisional Government, something that they had rejected the year prior. Then McLoughlin himself allowed for the HBC’s entrance into the government as well, while simultaneously moving HBC headquarters to Vancouver Island (but not, crucially, his own private holdings). American settlers, now confident in their dominance, responded with enthusiasm, implementing a bi-national oath for government officials, in which officials swore they would uphold Oregon’s laws “so far as they are consistent with my duties as a citizen of the United States or a subject of Great Britain.” A small minority of Americans, known as the “Ultra-Americas,” continued to try to keep all British influence out of the government at all costs, but they were outnumbered by – in McLoughlin’s words – “respectable Americans in the Settlement.” Essentially, most American citizens and British subjects got along just fine, and Oregon prospered – to such an extent that some American migrants contemplated declaring independence as an international country.

Oregon independence, of course, was not to be. In 1846, after President Polk backed down from his belligerent “54’40” or fight” stance, Great Britain and the United States agreed to divide Oregon at 49 degrees latitude. The Willamette Valley settlements became part of Oregon Territory. In an ironic twist, many Americans in Oregon lamented their new status. Some hated being a U.S. territory, with a U.S.-appointed governor – particularly galling because Oregon had once governed itself. Others believed U.S. annexation would allow for faster expansion onto indigenous land, but this backfired. In the bloody Cayuse War of the late 1840s, and the Yakima War of the mid-1850s, the U.S. Army often took the side of Native peoples, blaming American settlers for initiating the violence (which, ultimately, only briefly stemmed the tide of American appropriation of Native land). The HBC’s power and profits in British North America, meanwhile, continued to decline. McLoughlin himself chose to remain in American Oregon, where one observer celebrated him as a prominent “American citizen” by virtue of his deeds in the early 1840s, but noted that he could never be a “U.S. citizen.” The vagaries of Oregon identity before annexation could not match the binary of national identities after annexation.

Thomas Richards, Jr. is a David J. Weber Fellow in the Study of Southwestern American at the William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies at Southern Methodist University. He has a PhD from Temple University (Philadelphia, PA) and was a dissertation fellow at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies. He has published articles with the Pacific Historical Review and two of his chapters will soon appear in two edited volumes: Somewhere Between Citizens and Foreigners: Perceptions of Mormons in American Political Culture and Revolutions Across Borders: Jacksonian America and the Canadian Rebellion.

Works Cited

Elijah White’s letter can be found in the Elijah White Papers, MSS 1217, in the Oregon Historical Society in Portland. John McLoughlin’s correspondence is found in The Letters of John McLoughlin to the Governor and Committee, 3 Volumes, ed. E.E. Rich (Toronto: Champlain Society, 1943).

Secondary works on the dynamics within Oregon Country itself (as opposed to the diplomacy between Great Britain and United States over Oregon) remain sparse. More comprehensive accounts include Malcolm Clark, Eden Seekers: The Settlement of Oregon, 1818-1862 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1981), 139-176; John Hussey, Champoeg: Place of Transition: A Disputed History (Portland: Oregon Historical Society, 1967), 150-172; Robert Loewenberg, Equality on the Oregon Frontier: Jason Lee and the Methodist Mission, 1834-1843 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1976); Melinda Marie Jetté, At the Hearth of the Crossed Races: A French-Indian Community in Nineteenth-Century Oregon, 1812-1859 (Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 2015). The most comprehensive account of Oregon diplomacy remains David M. Pletcher, The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1973).

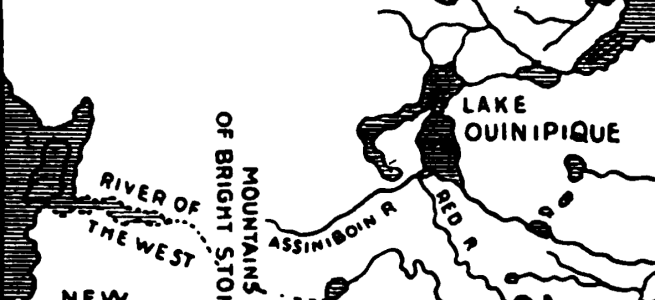

Cover Image: Jonathan Carver’s map of the River of the West, 1778, printed in John B. Horner, Oregon: Her History, Her Great Men, Her Literature. Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons.