Rachel Engl Taggart

In September 1775, over 1,100 Continental army officers and soldiers embarked on an expedition to Canada under the direction of Colonel Benedict Arnold to entice their neighbors to the north to join in the fight against the British empire. The men who volunteered for this mission just a few months into the Revolutionary War shared something in particular with the men who would later embark upon the Sullivan Expedition of 1779 to rout out loyalists and Indigenous Tory sympathizers in the interior of present-day New York State. Men from these two campaigns produced a usually high number of personal accounts describing their experiences that have helped historians not only to more fully understand the details of the campaigns, themselves, but also the daily experience of military life while on these specialized missions.[1] So the question becomes why—why did men who volunteered for the invasion of Canada and later the Sullivan expedition feel particularly compelled to keep track of their daily movements and activities?

To answer this question, this post focuses on the experience of Colonel Benedict Arnold’s forces during the Canadian campaign. Exploring the lives of these men who hailed from

New England, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, we can begin to see how this experience shaped the development of a cohesive community of men within the Continental army and the memory of the Revolutionary War for veteran soldiers.

In seeking a more comprehensive understanding of the experience of Continental soldiers in Canada, it is necessary to first consider how they ended up there in the first place. The journey to Canada would not only be the first experience for many men of a world outside of their local communities but also an empire in flux. Across the Atlantic, members of the British Parliament debated the development of an official policy of governing one of latest territories to the Crown’s expanding empire. The 1774 passage of the Quebec Act represented an attempt by Parliament to institute a policy by creating a permanent form of government for Canada and providing inhabitants with religious freedom and the liberty to follow French civil law.

The Quebec Act, though, stoked the fears of many colonists about a plot by the British to usurp their rights. John Adams, one of the opponents to the Act, voiced his concern to Congress arguing that it was “dangerous to the Interests of the Protestant Religion and of these Colonies.”[2] Following the outbreak of war between colonists and the British, members of the Continental Congress along with military leaders began to explore the idea of how they might try to convince Canadians to join in their fight against the Crown.

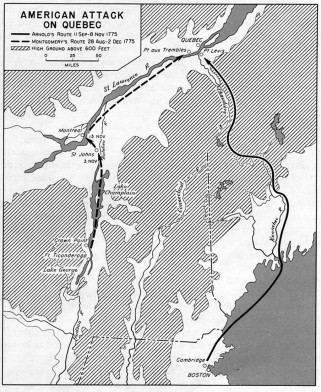

In the fall of 1775, a policy was enacted that involved a two-prong invasion of Canada: Colonel Benedict Arnold would lead a group of men through present-day Maine, while General Richard Montgomery and another contingent of men would travel north through Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point with the intention that their two forces would converge to mount a joint assault.

The first call for a detachment of men went out in the general orders issued by General George Washington to Continental army regiments on 5 September 1775. Though this initial call for volunteers did not specify either a location where this detachment would be headed or why one was needed, Washington did indicate that he sought “active Woodsmen” who were “well acquainted with batteaus.”[3] These clues, along with other discussions in camp, likely ignited the curiosity of many soldiers who eventually volunteered to participate in this specialized mission. One such soldier, Caleb Haskell, noted in his journal that orders were given a few days after Washington’s initial appeal to “raise men to go to Canada.”[4] With no indication of exactly why, Haskell recorded the following day that that he “enlisted under the command of Capt. Ward for the expedition to Quebec.”[5]

One of the first major campaigns of the Revolutionary War, the Canadian expedition provided the opportunity to truly coalesce men from different areas, including New England, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, into one fighting force representing the Continental army and the American patriot cause. Remembering the motley crew of men who embarked on the march to Quebec, John Henry, a private from Pennsylvania, described the New England soldiers who he now served alongside as “men were of as rude and hardy a race as ourselves, and as unused to the discipline of a camp, and as fearless as we were.” In recognizing the similarities between New England men and Pennsylvania men, Henry alluded to the conscious comparison that often took place once soldiers from different colonies encountered one another. As he described, “the principal distinction between us, was in our dialects, our arms, and our dress.” Though differences, like the ones Henry noted, did at times erupt into major issues for Washington and other officers to confront throughout the war, the members of this joint force seemed to more often look beyond their different backgrounds, as they came to rely upon each other to overcome the harsh conditions and little provisions on their mission to entice their neighbors to the north to join them in their fight for liberty.

More significantly, this was not just an affected show of cooperation but rather a genuine commitment among men who shared similar sentiments and the same goals. This communal experience provided the foundation for the close relationships that emerged among the participants of the Canadian campaign. As John Henry, the private from Pennsylvania, elaborated, he grew “to know many of them afterwards intimately” because of the close quarters they kept and the ordeals they shared both on march and later while as many were imprisoned after the failed assault on the British forces stationed at Quebec.[6]

Any excitement generated by the idea that the march to Canada would be a great adventure was soon dampened by the harsh conditions they faced just a few months into their journey. One soldier remarked that he and his fellow comrades found themselves “in a very misrabel Sittiuation [sic]” with “nothing to eat but dogs.”[7] One of the officers confirmed the soldiers’ desperation as he found a group of men “devouring a Dog

between them, and eating paunch, Guts, and skin.”[8] Though these conditions wore down their fortitude, they cemented a sense of mutuality among the men whose very survival depended on each other.

The soldiers under Arnold did not find any relief, either, upon crossing the border into Canada. While some local inhabitants snuck supplies to the desperate American forces, others resisted, as they chose to place their destiny in the hands of the British. Moreover, the failed attempt to confront the British forces in the midst of a snowstorm in December 1775 led to the imprisonment of over four hundred men. The prisoners tried to make the best of their situation as one described, “we live very Cold and desag[reeable] but imply our Selvs in all of plays [games] that we can think of.”[9] Those fortunate enough to have escaped imprisonment felt a deep sense of empathy for their comrades as they waited news “from our friends, the prisoners in the city.”[10] For the soldiers confined, as well as those who remained free, the extreme hardships they encountered left an indelible mark on the minds of these young men as their ordeal finally came to an end in the spring of 1776 when the remaining prisoners were released. The suffering the men had faced was clear to one of their officers who described them upon their release as “almost naked, and very Lousy … many of them unable to Walk, being lame in their knees lying so long in an unwholesome place.”[11] These individuals who had left hopeful and excited for a new adventure as they marched into a territory and world likely only known to them through books or perhaps even from tales of male relatives who may have served in the expedition to Louisburg in 1745 returned as different men.

Over forty years after the expedition to Quebec first began, Revolutionary War veterans appeared in courts throughout the United States to testify to their service in the Continental army in hopes of receiving a pension from the federal government under new legislation passed first in 1818 for impoverished and invalid veterans and later expanded in 1832 to all veterans who had provided at least one year of service during the war. The testimonies given by veterans of the invasion of Canada attest to lingering impressions the campaign had not only left on their bodies but also on their minds. In July 1821, a private during the Canadian expedition, James Melvin sent an impassioned letter chronicling his many years of service in the Continental army to obtain some form of financial assistance from the country for which he had sacrificed so much. Melvin described how he “traversed the wilderness during an inclement season” to arrive in Quebec in November 1775, from where he would be taken prisoner a few months later at the beginning of 1776. The veteran soldier succinctly described his eight-month ordeal as a prisoner in Canada as leaving him “destitute and worn down with hardship” because of the “costly confinement in a loathsome prison.”[12]

The pension files of Arnold’s veterans also highlight the continued bond these men shared because of their experience during the invasion of Canada. Several individuals provided testimonies to support the application of their former comrades, which suggests that even if these men had not kept in contact through all the years after the war, they were nevertheless able to find one another when the occasion to help arose. Though now living in New Hampshire after the war, John Sleeper testified that he was “well acquainted with Caleb Haskell,” who resided in Newburyport, Massachusetts at the time of his pension application. Sleeper corroborated Haskell’s claims of service in the Continental army arguing that they had served together in the same company as volunteers on the Quebec expedition.[13] In Sleeper’s pension application, another former member of the same company, William Dorr, came forward on his behalf and testified that they had been confined together after many Continental soldiers had been taken prisoner by the British in January 1776. Dorr noted that they were first confined “in the seminary, afterwards in the stone prison. We returned by water to New York & went afterwards into the Jerseys,” where they were finally released.[14] Again, even though these two men now lived in different states, New Hampshire and Maine, they nevertheless were able to find one another to provide corroborating testimonies for each other. Together these few examples reveal the emotional connection members of the Quebec campaign shared that remained ingrained in their memories of the war.

While the quest to encourage the inhabitants to join in the American cause during the Revolutionary War failed, the experience molded the men who shared in the extreme hardships they continuously faced throughout the campaign. And while many Americans sought to overlook one of the first great failures of the Continental army in favor of celebrating the great overall victory against the British, the veteran soldiers of the Canadian expedition kept the memory of their ordeal alive through their writings and their colorful testimonies, ensuring that their sacrifices would not be forgotten.

Rachel Engl is a Ph.D. candidate at Lehigh University, where she is completing her dissertation titled, “America’s First Band of Brothers: Friendship and Camaraderie within the Continental Army during the Revolutionary Era.” She has received several fellowships from institutions including the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon, the Lawrence Henry Gipson Institute for Eighteenth-Century Studies, and the McNeil Center for Early American Studies. Her work has been featured on the “Age of Revolutions” blog, and her recent talk at the Society of the Cincinnati was taped for C-SPAN.

Notes

[1] Rebecca Anne Goetz, “Private William Dorr’s March to Quebec: A Study in Historical Ambiguity” Honors Thesis, Bates College (2000): 27. Goetz notes that there were at least twenty personal accounts written by men who participated in the march to Quebec in 1775-6, though she does argue that some of these accounts may have been shared between men and different portions copied from one another. For the Sullivan campaign, there were at least twenty different personal accounts kept by soldiers. See James D. Folts, Jr., “The Sullivan Campaign: A Bibliography” University of Rochester Library Bulletin, vol. 32 (Winter 1979), available online: http://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/3568.

[2] “Heads of Grievances and Rights,” September 9, 1774, Founders Online, NARA, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-02-02-0041-0002.

[3] General Orders, September 5, 1775, The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 1, ed. Philander D. Chase. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985): 414–416.

[4] September 9, 1775, Caleb Haskell’s Diary: A Revolutionary Soldier’s Record before Boston and with Arnold’s Quebec Expedition, ed. Lothrop Withington (Newburyport: William H. Huse & Company, 1881), 10.

[5] September 10, 1775, Caleb Haskell’s Diary, 10.

[6] John Joseph Henry, Campaign Against Quebec Being an Accurate and Interesting Account of the Hardships and Sufferings of that Band of Heroes Who Traversed the Wilderness By the Route of the Kennebec, and Chaudiere River, To Quebec, In the Year 1775 (Watertown, NY: Knowlton & Rice, 1844), 15.

[7] November 1, 1775, Diary of a Common Soldier in the American Revolution, 1775-1783: An Annotated Edition of the Military Journal of Jeremiah Greenman, eds. Robert C. Bray & Paul E. Bushnell (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 1978), 18.

[8] November 1, 1775, Edwin Martin Stone, The Invasion of Canada in 1775, Including the Journal of Captain Simeon Thayer, Describing the Perils and Sufferings of the Army Under Colonel Benedict Arnold, in Its March Through the Wilderness to Quebec (Providence: Knowles, Anthony & Co., 1867), 15

[9] February 1-15, 1776, Diary of a Common Soldier, 25.

[10] January 16, 1776, Caleb Haskell’s Diary, 16.

[11] June 6, 1776, The Invasion of Quebec in 1775, 39.

[12] James Melvin, S33099, Revolutionary War Pension Files, NARA. All pension files listed were accessed through Fold3.

[13] Caleb Haskell, W19676, Revolutionary War Pension Files, NARA.

[14] John Sleeper, S18207, Revolutionary War Pension Files, NARA.

Cover Image: “Arnold’s column is shattered in fierce street fighting during the Battle of Quebec,” cover art made by Charles William Jefferys for The Father of British Canada: A Chronicle of Carleton, Vol. 12 (1916)

I am always interested in reading articles on the Arnold Expedition. Caleb Haskell is my 4x great grandfather. Interestingly, another 4x great grandfather, Dr. Azor Betts, was a Loyalist who quite possibly was with the Queen’s Rangers, The King’s Rangers, and DeLancy’s Cowboys. He fled to New Brunswick in 1783. His daughter and Caleb’s son got married barely weeks after the end of the War of 1812, and some years later moved to Newburyport, Massachusetts.

LikeLike

By the way, John Sleeper and Caleb Haskell were both 21 and from Newburyport, and had enlisted on May 2, 1775 (Caleb’s birthday) in Captain Ezra Lunt’s Company (the muster roll in the appendix of Caleb’s published diary says the 2nd, but in the diary Caleb says he enlisted on the 5th). According to a local historian, in the Preface of Lt. Paul Lunt’s Diary (Paul was Ezra’s brother and a lieutenant in his company) the company was spontaneously formed after a rousing sermon by Rev. Jonathan Parsons (presumably on Sunday, the 30th in the Old South Presbyterian Church). Unfortunately, the same “historian” goes on to say that Lt. Paul Lunt also went to Quebec and was captured, but a simple reading of the diary shows that Paul actually stayed with the company in Cambridge. Sleeper and Haskell signed up on the same day with Captain Samuel Ward (the son of the governor of Rhode Island) to go with Arnold.

LikeLike